The final series of the 2011 Orioles season was characterized by the completion of Boston’s collapse and further iconized by Robert Andino’s walk-off single falling just short of Carl Crawford’s glove. Buried by Andino’s heroics and the shortcomings of a presumed postseason favorite was the performance by Ryan Lavarnway, Boston’s rookie catcher who, in hitting two home runs –- the first two of his career — in the second game of the series, forced a meaningful finale.

Lavarnway’s first blast not only extended the Red Sox lead to four in the fourth, but also, guided by luck and facilitated by another fan’s fielding error, found its way into my glove, triggering negotiations with the Red Sox’ clubhouse.

By September of 2011, my chasing of home runs balls in the stands was more reflex and instinct than thinking and planning. With the season winding down, I had already reeled in eight home runs on the year, including a streak of one catch in three consecutive games as well as two in one game earlier in the month, both of which were covered by both local and national media.

With Lavarnway’s blast jumping off the bat, I leaped out of my seat, reflex and instincts taking over, ignoring the larger-than-usual late-season Camden Yards crowd that served only as obnoxiously-accented obstacles in both enjoying the game and catching home runs. Those obstacles didn’t impede me, however, as I tracked the ball down the steps and into one of the few open rows in the section to my right. My initial judgment of the blast was off as the ball began to sail over my head.

I place a lot of trust in my vertical leaping ability. Many times, in both batting practice and in chase of game home runs, I have needed to leave my feet. I can get higher than most and that compensates for the times I underestimate the distance of a blast. Even after three seasons and sharpened instincts and reflexes, balls sometimes surprise me and carry just beyond the apex of my vertical.

Seeing Lavarnway’s home run continue to carry, I jumped as high as I could, reached with my glove arm and hoped I would land with a baseball in the webbing. The ball was just out of my reach, carrying three rows deeper than where I stood.

SEE VIDEO OF THE HOME RUN HERE

When it came to ball hawking, I was as lucky in 2011 as anyone could be. The day after catching my third home run in three consecutive days, the Baltimore Sun’s Kevin Van Valkenburg opened an interview with me by jokingly asking if had bought any lottery tickets. I probably would have if I were old enough.

As far as I know – and seemingly as far as the internet knows – my streak of catching a home run in three consecutive MLB games has never before been matched and was considered as close to impossible as statistics allowed.

On top of the streak, I had caught five other home runs for a total of eight, making it the highest single-season total in a decade according to entries on MyGameBalls.com. Just as I tell everyone who asks, catching home runs is not all luck; there is a lot of skill and athletic talent involved as well as the aforementioned instincts and reflexes. However, some things – like catching one in three straight nights – have a good bit of luck mixed in.

Once again, luck was on my side in 2011 with Lavarnway’s home run carrying over my head. As a result of my desperation leap, I had made a 180-degree turn, my back facing the field. My leap also caused another veteran Baltimore ball hawk, standing rows above, to momentarily lose sight of the ball. Expecting me to make the catch, he turned his glove as if he were a catcher trying to block a fastball in the dirt, preparing himself for any possible ricochets off my glove. Instead, the ball, momentum unimpeded, bounced off the palm of his glove, falling perfectly into mine three rows below.

I try not to celebrate when I catch a home run hit by an opposing player. Sure, I am just as excited when I catch their home runs as I am when I catch ones hit by the Orioles, but I try not to show it. My usual celebration is just to raise the ball in the air to ensure everyone sees who caught it. That night, maybe out of the shock of how I caught the ball or because my mind was preoccupied with my next move, I did not raise the ball in the air and, instead, scurried up the steps to my backpack that I bring to every game.

In attending over fifty Orioles games a year and standing in left field for every round of batting practice, I could, as some jokingly tell me, “open my own sportinggoods store.” If sporting goods stores only sold used baseballs, then yes, I probably could.

You would be surprised at the purposes that batting practice balls have served for me. They have been used for my own rounds of batting practice and catch, for autographs, made into bracelets, given to younger kids at games, traded for extra giveaways during promotional nights and for free food from the all-you-can-eat sections, sold, given to ushers to get on their good sides, handed to attractive girls after writing my phone number on it (no, it never worked), and – most importantly – used as dupes.

When an opposing team hits a home run, everyone, because of some Wrigley Field tradition, pressures the person who caught it to “throw it back!” That is where the dupe comes into play. A person in their right mind should never throw back a game home run. You never know the historic significance the ball could hold years – or even innings – later. Also, no one in their right mind should ever pass on the opportunity to throw a baseball onto a Major League diamond without consequences. A dupe ball allows to you to do both: keep a piece of history and launch a baseball as far as you can onto a professional baseball field.

Hurrying before the next pitch was thrown, I dug through my bag for a batting practice ball. I found one that did not have any writing on it – void of the usual drawings of male genitalia or the occasional message to Adam Jones – and threw it as hard as I could onto the field. My average throw from left field makes it to J.J. Hardy at shortstop and that is far enough for me. A successful throw of a dupe ball is far and safe, avoiding the heads of all players on the field. Shortstop is perfect (as long as I do not hit Hardy).

There was no question that I had to make it appear that I threw this ball back onto the field. The home run extended the Red Sox lead in a game that they needed to win. I am sure that throwing back a home run has minimal-to-no effect on the momentum of the game. It fires-up the home fans for a few moments, but players probably could care less. Either way, if by some chance, in appearing to throw a home run onto the field, I could positively affect the game for the Orioles, I was going to do it.

Immediately after throwing the batting practice ball onto the field I realized I had made a huge mistake. Every player wants their first home run ball back; it is an accomplishment a majority of people will never achieve. Without having written on the batting practice ball before throwing it back, I was genuinely concerned that Lavarnway and the Red Sox would confuse the ball with the real one. The last thing I want is for a player to have a ball on his mantle, showing his grandchildren, telling them it is his first Major League home run only for it to be a batting fake ball that some teen caught in batting practice. Compensation for returning the ball was far from my thoughts.

As quickly as I had rushed to my bag after the catch, I hurried to grab the usher of my section – a friend of mine – with the ball in my hand. She knew what was happening.

“Is it his first?” she asked.

I confirmed.

A series of radio calls brought a Camden Yards “suit” to meet with me.

“This isn’t your first rodeo, is it?” he asked. Either he recognized me or noticed a certain expertise in my ball switching. We introduced ourselves and began business. He began by telling me he would give me an autographed bat “or something” for the ball. I countered.

I requested to meet Lavarnway in person and make the trade. That is what I always told myself I would ask for if I was put in the situation. In fact, when I caught Matt Wieters’ 20th home run of the season earlier in the year, I countered Jeremy Accardo’s offer of five used bullpen balls (seriously, Jeremy?) with a request to meet Wieters in person. Accardo agreed for Wieters and told me he would have him sign something for me. Not long after the game, I was taking my picture with Wieters, holding a black, autographed bat.

This time, however, my request was denied.

“That’s not going to happen,” The Suit replied.

That caught me off-guard. Why can I not meet him?

“They have everything on lockdown down there because they are …,” he explained, pausing to find the right word.

“Because they are choking,” I said, helping.

He confirmed.

I was certainly disappointed, but there were little positive outcomes if I forced the issue. If I demanded to meet Lavarnway, I’m sure he would have felt I was holding the ball for hostage. And if my demand was ultimately met, he would not be very happy to meet me. Also, if I make a bad impression in this meeting, it could potentially hurt my negotiations with this Suit down the road.

I agreed to his original offer of “a signed bat or something,” and was told that someone would come get me later in the game.

In the ninth inning, a supervisor came to my seat and told me I could bring one friend with me. He said he was not sure what was happening, but to follow him. Grabbing another Camden Yards regular, we headed to Home Plate Plaza, the entrance behind home plate that houses the elevators that lead to the press box and the clubhouse. Maybe they changed their minds. Maybe I was going to meet him. Why else would I have been told I could bring a friend? He was emphatic about the “only-one” part, too.

Waiting for the conclusion of the game, we watched Adam Jones battle Jonathan Papelbon with two outs. With Jones’ strikeout, fans poured through the Plaza and out the doors as we waited, not knowing what was going to happen. About fifteen minutes after the end of the game, The Suit appears from the elevator. In his hand was a signed bat; in the other, a signed ball.

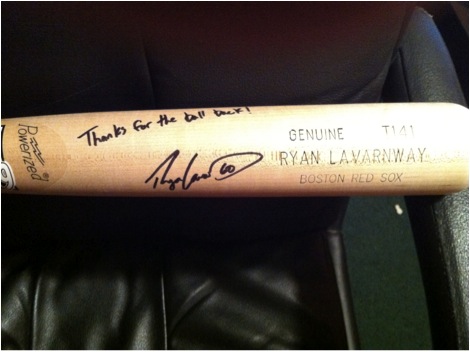

The bat was tan and inscribed. Above the autograph, Lavarnway inscribed “thanks for the ball back,” a message that makes the item invaluable.

I left that night without meeting Lavarnway, but happy with the decision I had made. Lavarnway deserved the ball more than I did.

The next night, in pre-game warm-ups, I got the attention of Lavarnway who was stretching in the bullpen, identifying myself as the one who caught the home run. He acknowledged me and asked if I received the items he signed for me. I confirmed and thanked him. He thanked me.

Good enough.