submitted by Danny Majerowicz (@dmajer347)

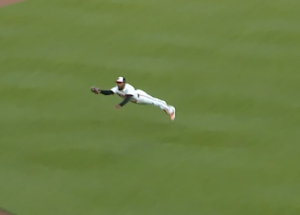

We are a month into the 2021 Major League Baseball season and the Baltimore Orioles have been, in some ways, a pleasant surprise and even wagerers have taken notice, ready to bet online. John Means pitched his way into Cy Young whispers. Cedric Mullins consistently flashes five tools. Matt Harvey looks closer to the Dark Knight version of himself than the oft-injured version. Such surprises have resulted in a near .500 record—much better than just about anyone expected. And while the first month of Orioles baseball has been rather enjoyable considering the team is still unapologetically in a rebuild, that status will remain unchanged. The emphasis will be on development, not winning, no matter how many wins the 2021 Orioles rack up early in the season.

Which leads me to the topic of this article. Before the season began, I expressed concern that the direction the front office took on infield defense over the off-season was confusing at best. On paper the infield defense looked worse, leading me to believe there could be potential for negative impact on pitcher development.

I want to look at just how that thesis is shaping up here. To do so, we will explore the number of pitches Orioles’ pitchers are throwing compared to the rest of the league, and try and figure out why the numbers are the way they are. We will see this is not a straightforward answer and the Orioles would do well to improve two areas to help limit stress on their pitchers.

The more pitches a pitcher throws, the more stress on their arm, which increases the risk of injury. That is why every team keeps pitch counts and limits innings for young pitchers. As the Orioles trek on in the rebuild, and more and more young pitchers take up space on their roster, they ought to be doing everything they can to keep pitch counts down.

The issue one month into the season is this: the Orioles pitching staff ranks twenty-second in pitches per inning at 16.85. For perspective, the Giants are first at 15.42. Now, you could point to the fact that the average pitches per innings across MLB is 17.02 and claim the Orioles are above average. However, the median is 16.62, as the teams in the bottom really skew the average (the Angels are last at a dreadful 17.9.)

Maybe you do not believe 16.85 is a big difference from 16.62. But consider, assuming every team plays 162 nine-inning games (which they will not, yet this will demonstrate the difference sufficiently), a team averaging 16.85 pitches an inning will amass 24,567 pitches over the season, whereas the team that throws 16.62 pitches an innings accumulates 24,232 pitches. That is an extra 335 pitches over a full season than the team directly in the middle of the pack.

In my opinion, that is simply too much risk for a rebuilding team to take with young pitchers.

I am sure some of you will point out that of course a rebuilding team will throw more pitches because on average, younger pitchers walk more batters, leading to higher pitch counts. You would be right that there is a correlation between walks and pitches thrown. However, that is not the end-all-be-all. Consider the Texas Rangers, who rank seventh in pitches per inning at 16.26. Texas also ranks first in BB/9. If walks tell the whole story, than why do the Rangers have such a disparity? Another example: the Nationals rank eighth in pitches per inning despite being twenty-second in BB/9! Cleveland is eleventh and nineteenth, respectively.

The Orioles continue this trend in the other direction. While being twenty-second in pitches per inning, they rank sixteenth in walks per nine innings. In other words, they are middle of the pack regarding walks, yet are in the bottom ten in pitches per inning.

So, we must ask ourselves: where do these extra pitches come from if walks fail to paint the whole picture?

Which brings us to defense. Converting potential outs into actual outs goes a long way in limiting pitches. Baseball Savant tracks outs above average, a stat that converts out probability into a range factor that demonstrates how effectively a fielder can turn a batted ball into an out based on how likely the batted ball was to be a hit. In short, a higher outs above average means the fielder is converting more plays into outs over the average fielder.

The Orioles, at this point in the year, considering all qualified fielders, are tied for twentieth overall in the stat at -2. In other words, the defense is costing Orioles’ pitchers outs.

Perhaps surprisingly, both the Orioles outfield and infield contribute a -1 to the total. Some caution though: not all numbers are created equal. Take out Ryan Mountcastle from the equation (which the Orioles have been doing lately) and the outfield outs above average goes up to a positive 1, a jump that would tie them for seventh with ten other teams.

The infield has an even uglier glaring weakness. In fact, Mancini (2), Mountcastle (1), Urias (1), Ruiz (1), and Galvis (0) combine for a +5 outs about average! That would be good enough for a tie of second among all MLB infields. But their numbers are dragged down by Pat Valaika (-1) and Maikel Franco (-5!). Franco’s number is tied for 183rd out of 187 infielders with a minimum of 10 attempts.

That is dreadful, and potentially harmful to a staff full of young pitchers.

To make this point crystal clear: the Giants, who throw the fewest pitches per inning, despite ranking 12th in BB/9, are the top team in outs above average. The Indians, ranking 11th in pitches per inning despite being 19th in BB/9, are 7th in outs above average. Defense matters in limiting pitches.

But that still does not tell the whole story. Remember the Rangers? They walk the fewest batters per BB/9 yet are only 7th in pitches per inning. They are 5th in outs above average. The Nationals, as stated above, are 8th in pitches per inning despite walking the 8th most batters, are 18th in outs above average. The Rangers play good defense and walk the fewest batters, yet throw more pitches than expected. The Nationals play bad defense, walk a bunch of hitters, and still are in the top ten of pitches per inning. How is this possible?

The link between these teams is strikeouts. Both rank in the bottom ten in K/9 (Washington ranking 21st and the Rangers 27th). Fewer strikeouts, again generally, lead to fewer pitches being thrown. The issue here for the Orioles story is they also rank in the bottom ten in K/9, sitting at 25th. So, if strikeouts are not a factor in the Orioles pitch count, what, besides poor third base defense contributes to the high number?

Look at Oakland. They rank 20th in pitches per inning despite walking the 9th fewest batters, rank 8th in outs above average, but are 23rd in K/9. What contributes to their high pitch rate?

One possible factor is their pitch framing. Baseball Savant tracks how effectively every catcher turns a ball just outside the zone into a strike. More strikes for a pitcher equals less overall pitches thrown, generally. Now, the A’s are not terrible at framing ranking 12th in overall framing, converting about 48 percent of balls just off the plate into strikes. But the discrepancy does allow us to explain why they throw more pitches than expected from their other factors.

We can also use the Rays as an example. By all accounts the Rays should be higher in pitchers per inning than they are (to be fair, they are 5th). However, they walk the 4th fewest batters and play the best defense according to outs above average while only racking up the 17th most strikeouts per nine innings. Why are they only 5th? Just look at their framing, where they rank 15th as their catchers convert about 47.5 percent of balls in the shadow zone into strikes.

And then there are the Orioles. Orioles’ catchers rank dead last in framing. It is not even close. Orioles’ catchers convert 42 percent of pitches in the shadow zone. The next lowest is 46%. Out of 59 qualified catchers, Chance Sisco ranks 57th in framing while Pedro Severino stands dead last. That is simply not good enough for a team that needs to do everything that they can to keep their pitchers healthy.

In summary, there are two major weaknesses that are costing the Orioles in extra pitches thrown. First, third base defense, largely due to Franco, has been abysmal. Secondly, Orioles’ catchers are the worst at getting extra strike calls from umpires. A pleasantly surprising season can get derailed quite quickly if a starting pitcher or two goes down, not to mention how it could potentially set back the rebuild.

The Orioles decision makers would be wise to address these issues before any worst-case scenario arises.